|

Because there were no known fossil non-avian dinosaur

fossils in rocks younger than the K–T boundary,

scientists originally concluded that non-avian dinosaurs became extinct immediately before, or

during the event. Recent discoveries of some non-avian dinosaur

fossils above the K-T boundary have been found, indicating that a few

species may have survived for a few hundred thousand years after the K-T

(see

Dinosaur Tombstone).

Scientists theorize that the K–T extinctions were

caused by one or more catastrophic events, such as massive asteroid impacts

(like the

Chicxulub impact), or

increased volcanic activity. Several impact craters and massive volcanic

activity, such as that in the

Deccan traps, have been dated to the

approximate time of the extinction event. These geological events may have

reduced sunlight and hindered photosynthesis, leading to a massive

disruption in Earth's ecology. Other researchers believe the extinction was

more gradual, resulting from slower changes in sea level or climate.

This lesson

will not examine the entire scope of the event. For a more complete

description, see the

K-T Extinction Event page on Wikipedia.

Duration

The length of time taken for the

extinction to occur is a controversial issue, because some theories about

the extinction's causes require a rapid extinction over a relatively short

period (from a few years to a few thousand years) while others require

longer periods. The issue is difficult to resolve because of the

Signor-Lipps effect;

that is, the fossil record is so incomplete that most extinct species

probably died out long after the most recent fossil that has been found.

Scientists have also found very few continuous beds of fossil-bearing rock

which cover a time range from several million years before the K–T

extinction to a few million years after it.

Causes

There have been several theories on

the cause of the K–T boundary which led to the massive extinction. These

theories have centered on either impact events or increased volcanism; some

include elements of both. There is even a scenario combining three major postulated

causes: volcanism,

marine regression, and

extraterrestrial impact.

By

far, the most widely accepted theory is the impact theory. In 1980 a

team of researchers consisting of Nobel prize-winning physicist

Luis Alvarez, his son

geologist Walter Alvarez, and chemists Frank Asaro and Helen Michel

discovered that sedimentary layers found all over the world at the

Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary contain a concentration of

iridium

many times greater than normal (30 times and 130 times background in the two

sections originally studied). Iridium is extremely rare in the earth's

crust, but it is abundant in most asteroids and comets. The Alvarez

team suggested that an asteroid struck the earth at the time of the K–T

boundary. There were other earlier speculations on the possibility of an

impact event, but this was the first evidence uncovered. Such an

impact would have inhibited photosynthesis by generating a dust cloud, which

would block sunlight for a year or less, and by injecting

sulfuric acid

aerosols into the

stratosphere, which

would reduce sunlight reaching the Earth's surface by 10–20%. It would take

at least ten years for those aerosols to dissipate, which would account for

the extinction of plants and

phytoplankton, and of organisms dependent on

them (including predatory animals as well as herbivores). Small creatures

whose food chains were based on

detritus would have a reasonable chance of

survival. The consequences of reentry of ejecta into Earth's atmosphere

would include a brief (hours long) but intense pulse of

infrared radiation, killing exposed

organisms. Global

firestorms may have

resulted from the heat pulse and the fall back to Earth of incendiary

fragments from the blast. High O2

levels during the late Cretaceous would have supported intense combustion.

The level of atmospheric O2

plummeted in the early Tertiary Period. If widespread fires occurred, they

would have increased the CO2

content of the atmosphere and caused a temporary

greenhouse effect once

the dust cloud settled, and this would have exterminated the most vulnerable

organisms that survived the period immediately after the impact.

Subsequent

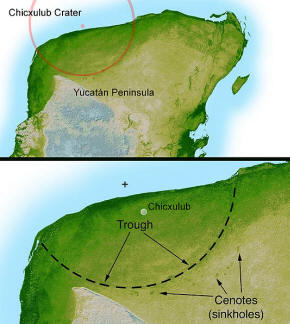

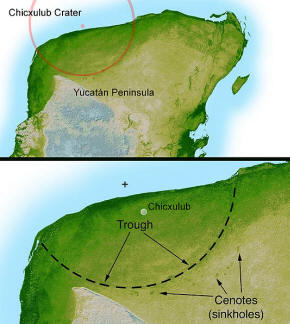

research identified the Chicxulub Crater buried under

Chicxulub on the coast

|

| Radar topography reveals the 180 kilometer (112 mi) diameter

ring of the crater; clustered around the crater's trough are

numerous sinkholes, suggesting a prehistoric oceanic basin in the

depression left by the impact. |

of

Yucatán, Mexico as the

impact crater which matched the Alvarez hypothesis dating. Identified in

1990, this crater is oval, with an average diameter of about 180 kilometers

(112 mi), about the size calculated by the Alvarez team.

The shape and location of the crater indicate further causes of devastation

in addition to the dust cloud. The asteroid landed in the ocean and would

have caused

megatsunamis, for which

evidence has been found in several locations in the Caribbean and eastern

United States—marine sand in locations which were then inland, and

vegetation debris and terrestrial rocks in marine sediments dated to the

time of the impact. The asteroid landed in a bed of

gypsum (calcium

sulfate), which would have produced a vast sulfur dioxide

aerosol. This would

have further reduced the sunlight reaching the Earth's surface and then

precipitated as acid rain, killing vegetation, plankton and organisms which

build shells from calcium carbonate For a more in-depth study of the

possible causes, see

Causes of Extinction.

Avian Dinosaurs (Birds)

Most paleontologists regard birds as

the only surviving dinosaurs.

However, all non-neornithean

birds became extinct, including flourishing groups like

enantiornithines and

hesperornithiforms.

Several analyses of bird fossils show divergence of species prior to the K–T

boundary, and that duck, chicken and ratite bird relatives coexisted with

non-avian dinosaurs. Neornithine birds survived

the K–T boundary as a result of their abilities to dive, swim, or seek

shelter in water and marshlands. Many species of birds can build burrows, or

nest in tree holes or termite nests, all of which provided shelter from the

environmental effects at the K–T boundary. Long-term survival past the

boundary was assured as a result of filling ecological niches left empty by

extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

Non-avian Dinosaurs

More has been published about the

extinction of dinosaurs at the K–T boundary than any other group of

organisms. Excluding a few controversial claims, it is agreed that all

non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the K–T boundary. The dinosaur fossil

record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no

decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous,

and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not

good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the choices.

Since there is no evidence that late Maastrichtian nonavian dinosaurs could

burrow, swim or dive, they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst

parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the K–T boundary. It is

possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would

have been deprived of food as both herbivorous dinosaurs would have found

plant material scarce, and carnivores would have quickly found prey to be in

short supply. The growing consensus about the

endothermy of dinosaurs (see

dinosaur physiology)

helps to understand their full extinction in contrast with their close

relatives, the crocodilians. Ectothermic ("cold-blooded") crocodiles have

very limited needs for food (they can survive several months without eating)

while endothermic ("warm-blooded") animals of similar size need much more

food in order to sustain their faster metabolism. Thus, under the

circumstances of food chain disruption previously mentioned, non-avian

dinosaurs died while some crocodiles survived. In this context, the survival

of other endothermic animals, such as some birds and mammals, could be due,

among other reasons, to their smaller needs for food, related to their small

size at the extinction epoch.

Several researchers have stated that

the extinction of dinosaurs was gradual, so that there were

Paleocene dinosaurs.

These arguments are based on discoveries in two rock formations.

First, the discovery of dinosaur remains in the Hell

Creek Formation up to 1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) above the

K-T boundary indicates some dinosaurs survived at least 40,000 years after

the event. More recent discoveries in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone indicate that

at least one species of hadrosaur lived past the K-T boundary, approximately 65.118 Ma (about

400,000 years after the

K–T event).

If you ordered the Test Pack, it is now time to

take Test 1.

Return to the

Old Earth Ministries Online Dinosaur

Curriculum homepage.

|