|

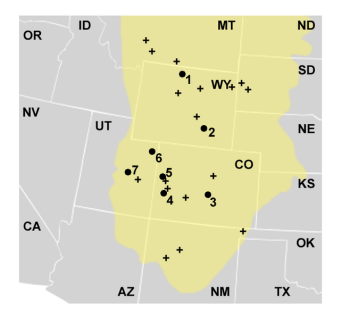

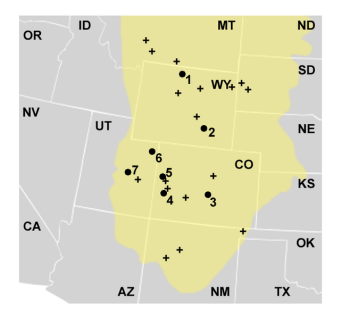

| Allosaurus Quarry Sites The

general extent of the Morrison Formation has been overlaid in

yellow. Historically or otherwise notable quarries where

Allosaurus remains

have been found include the numbered locations:

1) Big Al quarry, Big Horn Co., WY.

2) Como Bluff, Albany Co., WY.

3) Garden Park/Cañon City, Fremont Co., CO.

4) Dry Mesa Quarry, Delta Co., CO.

5) Grand Junction/Fruita, Mesa Co., CO.

6) Dinosaur National Monument West, Uintah Co., UT.

7) Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Emery Co., UT.

Other locations where

Allosaurus has

been found are marked with a "+".

|

Dinosaurs such as the theropods

Ceratosaurus,

Ornitholestes, and

Torvosaurus, the

sauropods

Apatosaurus,

Brachiosaurus,

Camarasaurus, and

Diplodocus, and the

ornithischians

Camptosaurus,

Dryosaurus, and

Stegosaurus are known from the Morrison.

The Late Jurassic formations of Portugal where Allosaurus is present

are interpreted as having been similar to the Morrison but with a stronger

marine

influence. Many of the dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation are the same

genera as those seen in Portuguese rocks (mainly

Allosaurus,

Ceratosaurus,

Torvosaurus, and

Apatosaurus), or have a

close counterpart (Brachiosaurus and

Lusotitan,

Camptosaurus and

Draconyx).

Allosaurus coexisted with fellow large theropods

Ceratosaurus

and Torvosaurus in both the United States and Portugal,

The three appear to have had different

ecological niches, based on anatomy and the location of fossils.

Ceratosaurs and torvosaurs may have preferred to be active around waterways,

and had lower, thinner bodies that would have given them an advantage in

forest and underbrush terrains, whereas allosaurs were more compact, with

longer legs, faster but less maneuverable, and seem to have preferred dry

floodplains. Ceratosaurus, better known than

Torvosaurus, differed

noticeably from Allosaurus in functional anatomy by having a taller,

narrower skull with large, broad teeth. Allosaurus was itself a potential food item to other carnivores, as

illustrated by an Allosaurus

pubic foot marked by the teeth of another theropod, probably

Ceratosaurus or

Torvosaurus. The location of the bone in the body

(along the bottom margin of the torso and partially shielded by the legs),

and the fact that it was among the most massive in the skeleton, indicates

that the Allosaurus was being scavenged.

Paleobiology

Life history

The wealth of

Allosaurus fossils, from nearly all ages of

individuals, allows scientists to study how the animal grew and how long its

lifespan may have been. Remains may reach as far back in the lifespan as

eggscrushed eggs from Colorado have been suggested as those of

Allosaurus.

Based on

histological analysis of limb bones, the upper age limit for

Allosaurus is estimated at 22 to 28 years, which is comparable to that

of other large theropods like Tyrannosaurus. From the same analysis, its maximum growth appears to

have been at age 15, with an estimated growth rate of about 150 kilograms

(330 lb)

per year.

Medullary bone tissue, also found in dinosaurs as diverse as

Tyrannosaurus and

Tenontosaurus, has been found in at least one

Allosaurus

specimen, a

shin

bone from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry. Today, this bone tissue is only

formed in female birds that are laying eggs, as it is used to supply

calcium

to shells. Its presence in the Allosaurus individual establishes sex

and shows she had reached reproductive age. By counting growth lines, it was

shown that she was 10 years old at death, so sexual maturity in

Allosaurus was attained well before maximum growth and size.

The discovery of a juvenile specimen with a nearly complete hindlimb

shows that the legs were relatively longer in juveniles, and the lower

segments of the leg (shin and foot) were relatively longer than the thigh.

These differences suggest that younger Allosaurus were faster and had

different hunting strategies than adults, perhaps chasing small prey as

juveniles, then becoming ambush hunters of large prey upon adulthood.

The thigh bone became thicker and wider during growth, and the cross-section

less circular, as muscle attachments shifted, muscles became shorter, and

the growth of the leg slowed. These changes imply that juvenile legs has

less predictable stresses compared with adults, which would have moved with

more regular forward progression.

Feeding

Paleontologists accept

Allosaurus as an active predator of large

animals.

Sauropods seem to be likely candidates as both live prey and as objects

of

scavenging, based on the presence of scrapings on sauropod bones fitting

allosaur teeth well and the presence of shed allosaur teeth with sauropod

bones.

There is dramatic evidence for allosaur attacks on

Stegosaurus,

including an Allosaurus tail vertebra with a partially healed

puncture wound that fits a Stegosaurus

tail

spike, and a Stegosaurus neck plate with a U-shaped wound that

correlates well with an Allosaurus snout.

However, as Gregory Paul noted in 1988, Allosaurus was probably not a

predator of fully grown sauropods, unless it hunted in packs, as it had a

modestly sized skull and relatively small teeth, and was greatly outweighed

by contemporaneous sauropods.

Another possibility is that it preferred to hunt juveniles instead of fully

grown adults.

Research in the 1990s and 2000s may have found other solutions to this

question.

Robert T. Bakker, comparing

Allosaurus to

Cenozoic sabre-toothed carnivorous mammals, found similar adaptations, such as a

reduction of jaw muscles and increase in neck muscles, and the ability to

open the jaws extremely wide. Although Allosaurus did not have sabre

teeth, Bakker suggested another mode of attack that would have used such

neck and jaw adaptations: the short teeth in effect became small serrations

on a saw-like

cutting edge running the length of the upper jaw, which would have been

driven into prey. This type of jaw would permit slashing attacks against

much larger prey, with the goal of weakening the victim.

Similar conclusions were drawn by another study using

finite element analysis on an Allosaurus skull. According to

their biomechanical analysis, the skull was very strong but had a relatively

small bite force. By using jaw muscles only, it could produce a bite force

of 805 to 2,148 N,

less than the values for

alligators (13,000 N),

lions

(4,167 N), and

leopards

(2,268 N), but the skull could withstand nearly 55,500 N of vertical force

against the tooth row. The authors suggested that

Allosaurus used its

skull like a hatchet against prey, attacking open-mouthed, slashing flesh

with its teeth, and tearing it away without splintering bones, unlike

Tyrannosaurus, which is thought to have been capable of damaging bones.

They also suggested that the architecture of the skull could have permitted

the use of different strategies against different prey; the skull was light

enough to allow attacks on smaller and more agile ornithopods, but strong

enough for high-impact ambush attacks against larger prey like stegosaurids

and sauropods.

Their interpretations were challenged by other researchers, who found no

modern analogues to a hatchet attack and considered it more likely that the

skull was strong to compensate for its open construction when absorbing the

stresses from struggling prey.

The original authors noted that Allosaurus itself has no modern

equivalent, that the tooth row is well-suited to such an attack, and that

articulations in the skull cited by their detractors as problematic actually

helped protect the

palate and

lessen stress.

Another possibility for handling large prey is that theropods like

Allosaurus were "flesh grazers" which could take bites of flesh out of

living sauropods that were sufficient to sustain the predator so it would

not have needed to expend the effort to kill the prey outright. This

strategy would also potentially have allowed the prey to recover and be fed

upon in a similar way later.

An additional suggestion notes that ornithopods were the most common

available dinosaurian prey, and that allosaurs may have subdued them by

using an attack similar to that of modern big cats: grasping the prey with

their forelimbs, and then making multiple bites on the throat to crush the

trachea.

This is compatible with other evidence that the forelimbs were strong and

capable of restraining prey.

Other aspects of feeding include the eyes, arms, and legs. The shape of

the skull of Allosaurus limited potential

binocular vision to 20° of width, slightly less than that of modern

crocodilians. As with crocodilians, this may have been enough to judge

prey distance and time attacks.

The similar wide field of view suggests that allosaurs, like modern

crocodilians, were ambush hunters.

The arms, compared with those of other theropods, were suited for both

grasping prey at a distance or clutching it close,

and the articulation of the claws suggests that they could have been used to

hook things.

Finally, the top speed of Allosaurus has been estimated at 30 to

55 kilometers per hour (19 to 34 miles per hour).

Social behavior

Allosaurus has long been regarded in the semitechnical and popular

literature as an animal that preyed on sauropods and other large dinosaurs

by hunting in groups.

Robert T. Bakker has extended social behavior to parental care, and has

interpreted shed allosaur teeth and chewed bones of large prey animals as

evidence that adult allosaurs brought food to

lairs for their

young to eat until they were grown, and prevented other carnivores from

scavenging on the food.

However, there is actually little evidence of gregarious behavior in

theropods,

and social interactions with members of the same species would have included

antagonistic encounters, as shown by injuries to gastralia

and bite wounds to skulls (the pathologic lower jaw named

Labrosaurus

ferox is one such possible example). Such head-biting may have been a

way to establish dominance in a

pack

or to settle

territorial disputes.

Although

Allosaurus may have hunted in packs,

it has recently been argued that Allosaurus and other theropods had

largely aggressive instead of cooperative interactions with other members of

their own species. The study in question noted that cooperative hunting of

prey much larger than an individual predator, as is commonly inferred for

theropod dinosaurs, is rare among

vertebrates in general, and modern

diapsid

carnivores (including lizards, crocodiles, and birds) very rarely cooperate

to hunt in such a way. Instead, they are typically territorial and will kill

and

cannibalize intruders of the same species, and will also do the same to

smaller individuals that attempt to eat before they do when aggregated at

feeding sites. According to this interpretation, the accumulation of remains

of multiple Allosaurus individuals at the same site, e.g. in the

Cleveland-Lloyd quarry, are not due to pack hunting, but to the fact that

Allosaurus individuals were drawn together to feed on other disabled or

dead allosaurs, and were sometimes killed in the process. This could explain

the high proportion of juvenile and subadult allosaurs present, as juveniles

and subadults are disproportionally killed at modern group feeding sites of

animals like

crocodiles and

komodo dragons. The same interpretation applies to Bakker's lair sites.

There is some evidence for cannibalism in Allosaurus, including

Allosaurus shed teeth found among rib fragments, possible tooth marks on

a shoulder

blade,

and cannibalized allosaur skeletons among the bones at Bakker's lair sites.

Brain and senses

The brain of

Allosaurus, as interpreted from spiral

CT scanning of an

endocast, was more consistent with

crocodilian brains than those of the other living

archosaurs, birds. The structure of the

vestibular apparatus indicates that the skull was held nearly

horizontal, as opposed to strongly tipped up or down. The structure of the

inner ear

was like that of a crocodilian, and so Allosaurus probably could have

heard lower frequencies best, and would have had trouble with subtle sounds.

The

olfactory bulbs were large and seem to have been well suited for

detecting odors, although the area for evaluating smells was relatively

small.

In popular culture

Along with

Tyrannosaurus,

Allosaurus has come to represent the

quintessential large, carnivorous dinosaur in popular culture. It is a

common dinosaur in museums, due in particular to the excavations at the

Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry; by 1976, as a result of cooperative

operations, 38 museums in eight countries on three continents had

Cleveland-Lloyd allosaur material or casts. Allosaurus is the official

state fossil of Utah.

Allosaurus has been depicted in popular culture since the early

years of the 20th century. It is top predator in both

Arthur Conan Doyle's 1912 novel,

The Lost World, and its

1925 film adaptation, the first full-length motion picture to feature

dinosaurs.

It later became the starring dinosaur of the 1956 film

The Beast of Hollow Mountain,

and the 1969 film

The Valley of Gwangi, two

genre

combinations of living dinosaurs with

Westerns. In The Valley of Gwangi, Gwangi is billed as an

Allosaurus, although

Ray Harryhausen based his model for the creature on Charles R. Knight's

depiction of a Tyrannosaurus. Harryhausen sometimes confuses the two,

stating in a DVD interview "They're both meat eaters, they're both

tyrants... one was just a bit larger than the other."

Allosaurus also made appearances in the

Hammer 1966 remake

One Million Years B.C. and the 1975 film adaptation of

The Land that Time Forgot. In nonfictional presentations,

Allosaurus appears in the second and fifth episodes of the

BBC television

series

Walking with Dinosaurs,

Jurassic Fight Club, and the

Walking with Dinosaurs special

The Ballad of Big Al which chronicles the life of the

Allosaurus

specimen nicknamed "Big Al".

Return to the

Old Earth Ministries Online Dinosaur

Curriculum homepage.

Shopping

Many fine

reproductions of Allosaurus teeth, claws, skulls, and even complete

skeletons, are available from several companies. Please click the

links below to visit their websites.

Bay

State Replicas - Three skull varieties, complete hand, complete arm,

complete foot, complete leg, humerus, jaw w/teeth, foot claw, finger claw,

1st, 2nd, and 3rd digit fingers

Black

Hills Institute - Complete skeleton, skull with neck, leg, femur, skull,

reproduction head (fleshed), tooth (in matrix)

|